Lessons To Be Learned in a Medical Device Inventor’s Journey

Sometimes medical device inventors need to travel back in time to analyze earlier innovators who have crossed the divide from being a dreamer to becoming a successful patent holder with regular annuities and royalties from their invention. But even when success strikes, its duration may be short lived offering us valuable lessons for those who follow similar paths.

Such is the case when examining the exploits of Alan R. Kahn, who unlike many of his contemporaries, did not slipstream technological breakthroughs to invent his product, but instead extracted his idea from basic physics.

What’s further interesting about his journey, is that it took nearly two decades before he kicked himself into action and got a modified version of his idea off the ground.

He first had the idea for a pressure management technique way back in 1964 to measure the elasticity of human skin for a study on aging. However, the medical corporation he worked for at the time felt it had no commercial application and his idea was stillborn.

Then, some two decades later during a discussion on intracranial pressure monitoring, he realized he could parlay his original idea into a new apparatus to monitor dangerous pressure increases in patients with head or spinal trauma, craniotomies, Reye’s syndrome, and certain drug intoxications.

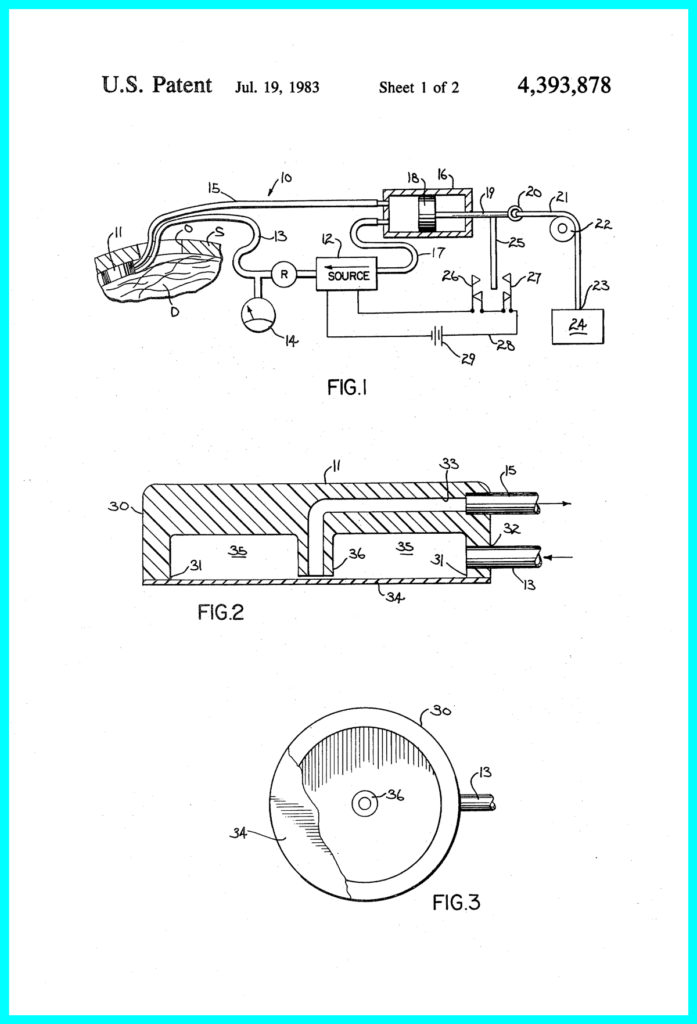

He immediately acquired a patent, naming his device a Pneumatic Extradural Intracranial Pressure Monitor.

Kahn believed his apparatus using a disposable sensor that would be accurate, rugged, and inexpensive to construct. It would eventually include a pneumatic system in a monitoring module that powers the sensor and provides self-checking and failure detection. He came to these conclusions using his knowledge of physics rather than any technological innovation that was happening in his industry sector at the time.

He then approached the leadership team in his present company to develop his idea under a royalty arrangement. Again, he was rebuffed. This second rejection spurred him into action. He left the firm and joined a research and development consulting firm as an equal partner with two of the founders.

All three of them sank personal time and funds into developing a prototype ICP monitoring system. After six months, they had an early version ready in their labs to perform preliminary tests on animals.

But what may be the salient point to come out Kahn’s experience in developing this medical device related to difficulties in marketing and financing the product.

“It was complicated by the fact that my partners and I were primarily interested in the invention process and did not wish to get involved in marketing,” said Kahn.

Part of the problem had to do with future innovation attached to the device. When the team approached venture capitalists they had to face up to the reality that the extradural method contained in the device was currently limited by the design of their prototype BUT also open to further enhancement as described in the patent.

Kahn was clear on this point in the final paragraphs of his patent application:

It will be readily apparent to those skilled in the art that a number of changes and modifications can be made without departing from the spirit of the present invention. For example, although the diaphragm is shown as glued in place closing the mouth of the sensor housing, it might be more advantageous in some applications to removably affix the diaphragm to the housing by using a retaining collar or similar means. Therefore, it is intended that the invention not be limited by any of the foregoing description but only by the claims which follow.

This evolutionary capability was lost on venture capitalists, who could not fully project how an improved product would affect market growth.

“Therefore, conservative sales projections were used in the business plan. These projections made the venture less attractive and affected our ability to obtain funding,” said Kahn.

But as with most successful entrepreneurs the story did not end there. The three medical device inventors finally procured a joint venture with a biomedical company called Meadox which had the necessary firepower to manufacturer the required sensors and also saw their prototype as a way to to enter the market for electronic products.

In a nutshell, the system had been designed as a sophisticated microprocessor-based instrument that all parties felt at the time could successfully penetrate the market.

According to Kahn, each of the three partners in the firm owned 9 percent of the new joint venture company and shared a royalty on product sales.

“Our & company received a contract from the joint venture company to develop the product and subsequently to manufacture the electronic portion of the system until such time as the contractors learned more about the product and could take over all of the manufacturing.”

But although the team of three did reach some financial success with their product, with steady sales in the United States, Meadox ultimately decided to discontinue the product line as it did not fully align with the strategic vision of the company.

While this is perhaps not the perfect ending you were hoping for with regards this medical device innovator, it does illustrate the power of time, ideas, royalties, joint ventures and the courage to use personal savings to fund a great idea.

It is also worth noting the length of time Kahn took before his seedling idea burst into life 20 years later. Incredibly, within six months he had a prototype and was knocking on venture capitalist doors.

Perhaps the biggest lesson here is to move quickly with your idea even when giant corporations throw shade on your budding inventions. Kahn got a second shot at glory but who knows what would have happened if had moved more quickly the first time around.

https://www.medicaldevicepatentattorneys.com/2018/07/lessons-to-be-learned-in-a-medical-device-inventors-journey/trackback/